Verification of DPRK Nuclear Disarmament: The Pros and Cons of Non-Nuclear-Weapon States (Specifically, the ROK) Participation in This Verification Program

John Carlson1, A Member of Asia Pacific Leadership Network for Nuclear non-proliferation and Disarmament (APLN)

PSNA Working Paper Series (PSNA-WP-7)2

May 20, 2019

Summary

In the expert and diplomatic communities, it is generally considered that disarmament verification should be undertaken as far as possible on a multilateral basis. Partly this reflects experience with the International Atomic Energy Agency’s safeguards system, and partly it reflects the view of non-nuclear-weapon states that international participation is required to ensure transparency and credibility in the disarmament process. The main argument against this is proliferation risk from the diffusion of proliferation-sensitive information. However, a number of aspects of disarmament verification will not involve sensitive information, and where sensitive information is involved there are ways of enabling effective verification while protecting such information.

As yet no specific details have been negotiated on how nuclear disarmament in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) will proceed, and how this will be verified. Whatever is negotiated, the international community will certainly want assurance of the integrity of the verification process. In particular, the ROK has a very direct interest in what is happening across the DMZ and has every reason to be involved in the disarmament effort. This paper discusses how this can be possible consistent with non-proliferation principles.

1. Introduction

As yet no specific details have been negotiated on how nuclear disarmament in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) will proceed, and how this will be verified. Internationally, there is no established model for conducting and verifying nuclear disarmament. There have been bilateral arms control agreements between the United States and Russia (or the Soviet Union), but these are of limited scope compared with what would be required for complete disarmament.

To date the only precedent for a state that had produced nuclear weapons disarming completely is South Africa, which dismantled its warheads secretly, and submitted the recovered fissile material (highly enriched uranium – HEU) to International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) safeguards as part of joining the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). Other precedents are:

(a) Ukraine, Belarus and Kazakhstan, which at the dissolution of the Soviet Union had Soviet nuclear weapons on their territories and agreed to transfer these weapons to the Russian Federation; and

(b) Iraq, Iran and Libya which were found to have nuclear weapon programs at varying stages of development.3

None of these precedents is comparable to the situation of the DPRK. Accordingly, whatever process is developed for the DPRK will be a pioneering effort, important in itself and also in helping to set a precedent for eventual disarmament in other nuclear-armed states.

In 2015 the International Partnership for Nuclear Disarmament Verification (IPNDV) was established to facilitate international collaboration on verification approaches and methods in support of nuclear disarmament. So far, the IPNDV has focused its studies on a specific aspect – monitoring and inspection of a notional nuclear weapon dismantlement process, what it calls the Basic Dismantlement Scenario. The IPNDV has not yet placed this dismantlement process into a broader disarmament framework. However, there has been substantial discussion of this subject within the verification expert community. Drawing on these discussions, this paper outlines a model framework for disarmament verification, discusses how this might apply to the DPRK, and discusses who might be given responsibility for the various verification tasks.

In the expert and diplomatic communities, the general view is that disarmament verification should be undertaken as far as possible on a multilateral basis. The establishment of the IPNDV reflects this view – from the outset the IPNDV has been focused not just on developing disarmament verification, but specifically how non-nuclear-weapon states can be involved in such verification.

Partly this reflects the experience gained with the IAEA safeguards system, which has a multilateral inspectorate, and partly it reflects the view of non-nuclear-weapon states that international (that is, multilateral) participation in nuclear verification is required to ensure transparency and credibility in the disarmament process. It is a matter of trust – non-nuclear-weapon states are not prepared to leave it to the nuclear-weapon states to inspect each other. The main argument in favor of non-nuclear-weapon state participation in nuclear disarmament verification, therefore, is to ensure international confidence in the integrity of the process.

The main argument against non-nuclear-weapon state involvement is the risk of proliferation arising from the diffusion of sensitive information. Some states, notably Russia, have taken a firm position against non-nuclear-weapon state involvement, maintaining disarmament verification can be undertaken only by personnel from nuclear-weapon states. However, this position fails to consider two key factors:

(a) a number of aspects of disarmament verification will not involve classified or proliferation-sensitive information, and in this case, there should be no objection to a multilateral process. For example, once ex-weapons nuclear material is in non-classified form and composition, it is no different to other comparable nuclear material and can be safeguarded accordingly – see the discussion in section 3 below; and

(b) where classified information is involved, it may well be possible to develop approaches and methods that enable effective verification while ensuring such information is fully protected.

In developing multilateral verification, therefore, the key issue to address is protection of classified information – how to ensure that involvement of non-nuclear-weapon state personnel in disarmament verification does not result in them acquiring nuclear weapon designs and know-how, which would be a violation of the NPT (discussed further in section 6). This is a particular focus of the IPNDV’s current work. It is absolutely crucial to both nuclear-weapon states and non-nuclear-weapon states to ensure effective protection of classified information – but states should be prepared to consider on their merits internationally-developed approaches to meet this objective.

In the case of the DPRK, the international community as whole (which predominantly comprises non-nuclear-weapon states) certainly wants assurance of the integrity of the verification process: apart from anything else because this is an important precedent for future disarmament efforts in the nuclear-weapon states. In particular, the Republic of Korea (ROK) has a very direct interest in what is happening across the DMZ and has every reason to be involved in the disarmament effort. This paper will discuss how this can be possible consistent with the NPT’s non-proliferation principles.

2. A model approach to nuclear disarmament

A generic approach to nuclear disarmament in a state would look something like this:

Stage 1 Cease production of fissile materials (HEU, separated plutonium – Pu)

(a) Declaration of all fissile material production facilities (enrichment and reprocessing facilities).

(b) Monitoring of these facilities to ensure production has ceased.

(c) In addition, tests of nuclear weapons and nuclear-capable missiles are to be terminated

– these tests are not covered by this paper.

Stage 2 Declaration of all nuclear material and all nuclear facilities

(a) Nuclear material – (i) total quantities per material category for all nuclear material in the state, including in warheads; and (ii) inventories at each nuclear facility

– total material per category (HEU, Pu) in warheads or military custody would be black boxed – the overall quantity within the military program would be declared, but without any breakdown by forms and locations;

■ this is because such information is sensitive and the state is unlikely to be prepared to declare it – of course if the state is prepared to give any details these would be extremely useful for verification purposes;

■ materials in warheads would not be available for verification until the warheads are dismantled (stage 5).

(b) Nuclear facilities – enrichment and reprocessing facilities should be declared in stage 1. Here all related facilities would be declared: reactors, fuel fabrication, conversion, mines/mills, storage, radwaste, etc.

(c) Historical nuclear material flows (production, consumption, losses)

– declarations, and supporting documentation, will be required in due course, but are not essential at the outset.

(d) Nuclear-related locations – declarations including:

– centrifuge R&D;

– centrifuge manufacturing;

– activities, items and materials covered by the IAEA Additional Protocol;

■ Annex I – items and materials specially prepared for nuclear use;

■ Annex II – dual-use items and materials;

– dual-use activities with potential nuclear weaponization application (based on the Iran JCPOA4).

(e) Tritium – declaration of relevant facilities (reactors, separation plant) and material flows also required in due course

– by stage 6 – earlier if production is proscribed at outset.

Stage 3 Inspections of declared facilities and related nuclear materials

(a) Where facilities are shut down/decommissioned – status to be verified.

(b) Where facilities remain in operation – inspections to verify they are operated as agreed (all nuclear material under safeguards; quantity and quality limits if applicable).

(c) Nuclear materials – safeguards to verify that materials remain in peaceful use and are transferred only to safeguarded locations and activities.

(d) Nuclear-related locations – activities at these locations should be terminated if the related nuclear activity (e.g. enrichment) is shut down. Inspections are required to verify shutdown, or that continuing activities are as agreed.

(e) This stage would also include establishment of a procurement channel where required for agreed nuclear-related activities and potential weaponization activities.

Stage 4 Excess nuclear materials in military program to be declared and removed from the state or transferred irreversibly to the safeguarded nuclear program

(a) There should be no valid reason for the state to retain separated plutonium. This would be removed from the state.

(b) Likewise, there is no valid reason for the state to retain HEU. This would be removed from the state. If the state is operating reactors requiring low-enriched uranium (LEU) fuel, the state could be supplied with LEU fuel corresponding to the quantity of HEU removed.

Stage 5 Progressive reduction in warheads (and missiles)

(a) Declaration of types and numbers of warheads and missiles will be required at an appropriate time (arrangements regarding missiles are not covered in this paper).

(b) Warheads are to be dismantled, and fissile materials are to be converted to unclassified forms and treated as excess materials (see stage 4 – materials to be verified and removed from the state).

(c) An issue to be negotiated is how dismantlement would be monitored/verified

– the usual concept is for warheads to be dismantled by the possessor state under black box/chain of custody arrangements, so the verifying entity can confirm that a warhead entered dismantlement and a corresponding quantity of fissile material exited.

Stage 6 Verification activities to provide assurance against existence of undeclared nuclear facilities and nuclear materials

(a) This is likely a contentious area as it requires intrusive activities including challenge inspections. The state needs to understand this is a necessary aspect of verification, without which confidence is not possible.

The state can be assured that a mandate to look for undeclared facilities and materials is not carte blanche for access anywhere for any purpose. In the verification context undeclared means something that should have been declared in accordance with the agreements applicable at the time in question.

Obviously until the state is required to give up all its warheads it will have some nuclear material it is not yet obliged to submit for inspection – verification activities will not be seeking to locate items and materials unless the state is required to declare them and has not done so. The purpose of verification against undeclared facilities and materials is to detect possible violations of applicable agreements.

(b) This stage will include establishing a historic nuclear materials balance, drawing on declared material flows (stage 2 (c)), facility operating records, sampling and analysis of materials, interviews of personnel and related activities.

(c) Activities to provide assurance against undeclared warheads and missiles will also be required but are not covered in this paper.

(d) Also required, but not covered in this paper, are programs, and appropriate verification/monitoring, to, inter alia:

– convert nuclear weapons-related labs, workshops and factories to peaceful purposes;

– redeploy specialists from the nuclear weapon program to peaceful purposes;

– track key specialists to ensure they don’t become involved with nuclear weapon programs elsewhere.

Stage 7 End of the disarmament process – the state is shown to meet the requirements for a non-nuclear-weapon state

At the end of the disarmament process the state would become a non-nuclear-weapon state. In the case of a non-NPT party the state should join the NPT. In either case – whether a former non-NPT party or a former NPT nuclear-weapon state – the state would be a non-nuclear-weapon state, subject to the most rigorous form of IAEA safeguards.

Recognising that the state had nuclear weapon capabilities (therefore the capability to rebuild its nuclear weapon program – and even the possibility that it has successfully hidden parts of its former program), it will also be subject to additional verification, confidence-building and transparency measures, including those referred to in 6 (d) above.

3. Applying this model to the DPRK

As yet it is not known if agreement can be reached with the DPRK for applying this model. It would be possible to apply a more limited version initially, reflecting more limited goals (for example, cessation of fissile production, dismantling of a specified number of warheads). However, as discussed in a complementary paper, Denuclearizing North Korea: The Case for a Pragmatic Approach to Nuclear Safeguards and Verification (see References), achievement of complete disarmament will require all of the elements outlined in the model.

Who should be responsible for undertaking the various monitoring and verification tasks? Most of these tasks are the same as or very similar to activities conducted by the IAEA in the implementation of safeguards around the world. While these tasks would not necessarily be undertaken by the IAEA, there seems no in-principle reason why they should not be. For example:

● Stage 1 – cease production of fissile materials

This requires declaration of all enrichment and reprocessing facilities, and monitoring of these to ensure they are no longer operating. Monitoring the status of nuclear facilities is a standard part of IAEA safeguards procedures. The IAEA has previously undertaken monitoring of the reprocessing plant and 5 MWe reactor at Yongbyon.

● Stage 2 – declaration of all nuclear material and all nuclear facilities, and nuclear-related activities, items and materials

Receipt and analysis of declarations of nuclear facilities, and nuclear material inventories and flows, are a standard part of IAEA safeguards procedures.

While the IAEA does not usually verify inventories and flows of non-nuclear materials such as tritium (stage 2 (e)), it could do so, INFCIRC/66 safeguards agreements5 allow for this possibility.

● Stage 3 – Inspections of declared facilities and related nuclear materials

Inspections to verify the operational status of nuclear facilities, and to verify nuclear material inventories and movements, are a standard part of IAEA safeguards procedures. Where proliferation-sensitive activities are involved (such manufacturing of centrifuge components) it may be necessary to use inspectors drawn from technology-holder states.

● Stage 4 – Excess military nuclear materials to be declared and transferred from the DPRK or transferred irreversibly to safeguarded program

This involves verifying materials that are declared excess, and tracking them to ensure they are transferred from the DPRK or are placed under safeguards in the DPRK and remain under safeguards. These activities are similar to standard IAEA safeguards procedures.

● Stage 6 – Verification for assurance against possible undeclared nuclear facilities and materials

This involves a range of activities, such as:

– information collection and analysis (including open-source information, satellite imagery, possibly wide-area environmental sampling, information from states) looking for possible indicators undeclared nuclear activities and materials;

– establishing a historic nuclear materials balance, looking for discrepancies and inconsistencies in declared information;

– investigation of possible indicators, including through inspector access to suspect locations, using mechanisms such as complementary access, technical visits, or special inspections.

All of these activities are part of standard IAEA safeguards procedures. Special arrangements may be required if the IAEA has to investigate possible weaponization activities (this may require specially cleared inspectors from nuclear-weapon states). Such arrangements have applied during IAEA investigations in Iraq, Iran and Libya, and in South Africa.

● Stage 7 – The DPRK qualifies as non-nuclear-weapon state

At this point standard IAEA safeguards arrangements will apply, as in any other non-nuclear-weapon state. As noted above, additional confidence-building and transparency measures will also be required.

Monitoring and verification that would not be undertaken by the ILEA

● Stage 1 (c) – no tests of nuclear weapons and nuclear-capable missiles

Activities for detection of any nuclear tests would be undertaken by the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO). There is no international inspectorate for detection of missile tests, this is a matter for national intelligence and technical means.

● Stage 2 (d) – monitoring at nuclear-related locations

In appropriate cases might be undertaken by supplier states or through cooperation among the authorities of relevant states – or through establishment of a Joint Commission along the lines of the JCPOA.

● Stage 3 (e) – procurement channel

Clearance and monitoring of procurement might be undertaken by supplier states or through cooperation among the authorities of relevant states – or through a Joint Commission.

● Stage 5 – Reduction and dismantlement of nuclear warheads

This is the main area where new verification arrangements need to be developed. This is the current focus of IPNDV studies. (Stage 5 would also include destruction of missiles, but this is not covered by this paper).

4. Dismantlement of nuclear warheads

This is an area of high secrecy from two perspectives:

(a) National security – while the state continues to hold nuclear weapons, it does not want others to learn specifics of its capabilities (including questions of warhead yield and reliability);

(b) Non-proliferation – there is an over-riding international interest to ensure that information potentially helpful to a proliferator is totally protected.

These considerations, as well as the requirement for verification effectiveness, will influence the specifics of the verification arrangements on which agreement can be reached.

A threshold question is whether the DPRK is prepared to simply hand over warheads (for example, to a team of specialists from the nuclear-weapon states). If so, monitored dismantlement would not be necessary. However, it is likely the DPRK will be concerned to protect national security information, so for this paper it is assumed the DPRK will not hand over intact warheads.

Safety must be paramount Apart from DPRK sensitivities, a compelling argument for warheads to be dismantled by DPRK personnel is for reasons of safety. First, transporting the warheads elsewhere could be dangerous. Second, those who made the warheads know their design and characteristics and are in the best position to dismantlement them safely. Particular care will be required to build a dismantlement facility that provides adequate protection for surrounding populations in case of accidental explosion (it will also be essential to warn neighbouring states when dismantlement operations are proposed).

A further threshold question is whether verification of warhead dismantlement is essential. The immediate reaction is, of course it is. However, this is not a straightforward issue, it depends on the objective sought. If the objective is immediate elimination of an agreed number of warheads, then monitored dismantlement will be required. On the other hand, if (as is likely) it is assessed that the DPRK has limited holdings of fissile material (so has limited ability to replace dismantled warheads if it sought to do so), it might be considered acceptable to have dismantlement without monitoring, with the DPRK simply handing over the quantities of HEU and plutonium estimated for the agreed number of warheads.

There may be some concern that dismantlement by the DPRK without monitoring would leave the possibility that warheads declared to be dismantled have really been concealed – but this is an issue anyway, because the number of warheads actually produced by the DPRK is not known (so calling for the elimination of a specific number of warheads may be of uncertain utility). It will probably not be until the end of the disarmament process that there is sufficient information to conclude that all warheads and nuclear materials are satisfactorily accounted for.

This paper is not recommending against requiring monitored dismantlement, but simply noting that if there are difficulties in establishing monitored dismantlement, the pros and cons could be further considered. In support of monitored dismantlement, it can be pointed out to the DPRK this would have a substantial confidence-building benefit.

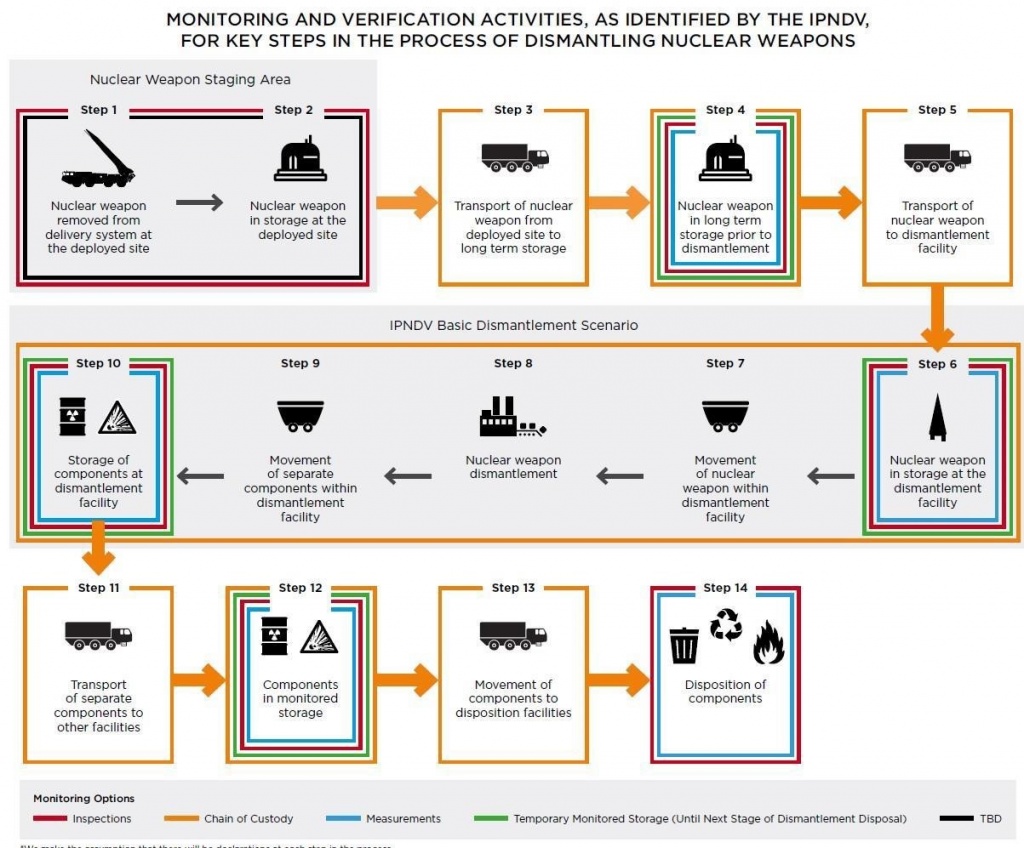

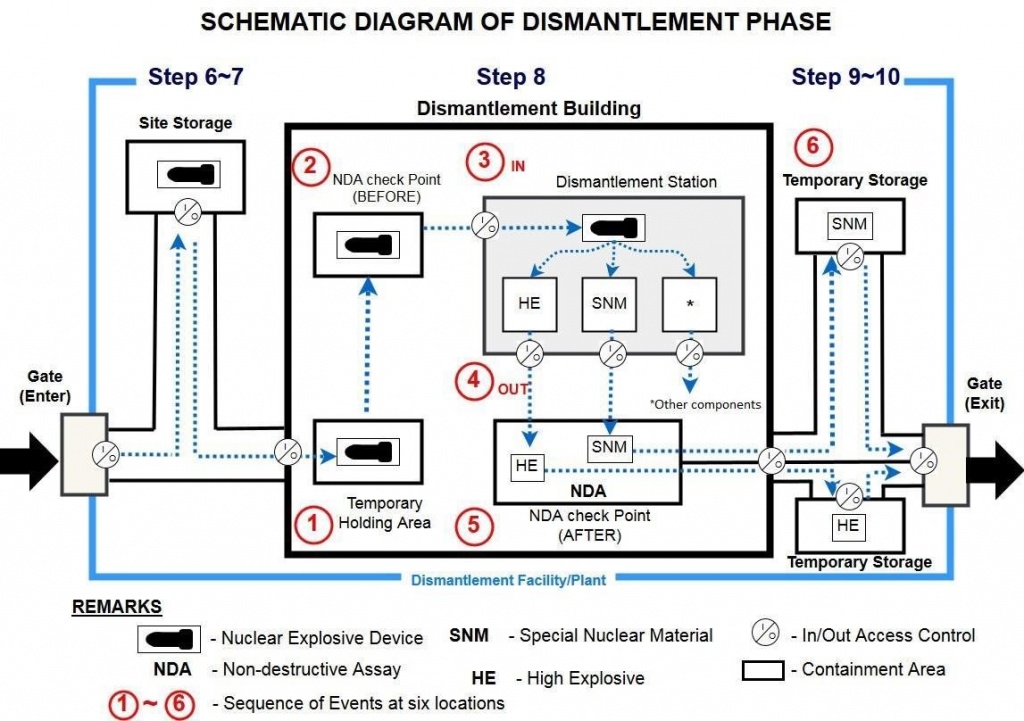

The following diagram shows IPNDV’s visualization of key steps in the process of dismantling nuclear weapons.6

The concept of monitored warhead dismantlement

The basic approach is that the state would be responsible for dismantling its own warheads, thereby ensuring it maintains secrecy over warhead characteristics (design, fissile material quantity, quality and shape, and so on). Dismantlement would take place in a black box – this black box would comprise a specially constructed facility together with appropriate procedures. Movement of warheads into the facility and objects and materials out of the facility would be monitored by inspectors of the verifying entity (see section 5 below). All fissile material exiting the facility would be transferred to monitored storage and disposition.

The generic concept is illustrated in the following diagram from IPNDV documentation.7

A description of monitored warhead dismantlement is as follows:

(a) Dismantlement facility

This facility would be specially designed and constructed for safe and secure dismantlement of warheads in circumstances that enable confidence that all movements of objects and materials into and out of the facility can be monitored effectively. Inspectors would be given the facility design information and would have access during construction to verify there are no hidden exit pathways (doorways, pipework) or places where objects and materials could be hidden for subsequent removal. Inspectors would have regular access to the facility to check there have been no alterations and that objects and materials are not being retained within the facility.

In the (unlikely) event that warhead reductions proceed at a faster pace than the construction of the dismantlement facility, warheads could be held in monitored storage until the dismantlement facility is ready.

(b) Confirmation that an object entering the facility is a warhead

It is assumed the DPRK will wish to conceal the specific characteristics of its warheads. There are two possible situations:

(i) the DPRK presents a warhead to inspectors to check prior to dismantlement; or

(ii) the DPRK presents a container declared to contain a warhead. In the latter case standardized containers would be used, approved by inspectors for the purpose.

In either case inspectors would perform a range of measurements designed to confirm, without revealing classified information, that (i) the object presented is a warhead or (ii) the container holds a warhead. This approach, described as attribute measurement, is discussed below.

(c) The dismantlement process

DPRK personnel would dismantle each warhead, and re-form the fissile components (weapon cores, or pits) into unclassified shapes and mass (for example, 1 kg or 2 kg buttons), and possibly convert the materials into other forms (for example, from metal to oxide).

Because re-forming or converting the fissile material involves very different processes to dismantlement (for example, melting or chemical reactions), it is possible the DPRK may wish to undertake these processes in a separate facility. In this case it would be necessary to establish a system for verifying transfers of materials from one facility to the other and maintaining a chain of custody over these materials.

(d) Transfer of fissile material from the dismantlement facility to storage and disposition

When plutonium or HEU is ready to be transferred from the dismantlement facility, inspectors would measure the material to confirm its mass and isotopic composition. Inspectors would also check the cumulative mass for outgoing transfers in a given period to ensure this is at least equal to the cumulative threshold values for the warheads that entered the dismantlement facility during the period.

There will be some uncertainties in deriving a material balance between fissile materials entering and exiting the dismantlement facility, because material inputs will be calculated on minimum threshold values for mass and isotopic composition, while material outputs will be precisely measured. Because the threshold values are minimums, total material outputs can be expected to exceed total inputs. Total output may be reduced by conversion losses, but these would be very small (and it should be possible to confirm losses by measurement of wastes and discards).

(e) Rigorous monitoring of all movements into and out of the dismantlement facility

In addition to declared transfers of warheads into the facility, and declared transfers of nuclear materials out of the facility, all other movements of objects and personnel will require rigorous monitoring to ensure there are no undeclared movements of nuclear materials.

(f) Regular inspections of the dismantlement facility

Inspectors will need to check for undeclared alterations to the building, and for possible concealment of nuclear materials. As inspectors should not have the possibility of access to classified information, these inspections would be conducted between dismantlement campaigns, when there are no warheads or intact pits in the facility.

Attribute measurement

Attribute measurement is an approach by which inspectors can take measurements to confirm whether an object is a warhead, or a container holds a warhead, without accessing classified information. The approach is based on information barriers, enabling instruments to be used to measure for expected attributes without revealing classified details to the inspector.

A series of attributes would be defined for particular warhead types. The attributes would be described as threshold numeric values, for example:

(i) a mass of plutonium above a specified threshold;

(ii) a Pu-240/Pu-239 ratio below a specified threshold;

(iii) a mass of U-235 above a specified threshold;

(iv) a U-235/U-238 ratio above a specified threshold;

(v) presence of high explosives.

Modified instruments, that would give a go/no go (or green light/red light) indication but not specific readings, would be used for these measurements. The result is that inspectors would be confident that a warhead containing “x” kilograms or more of weapon grade plutonium, or “y” kilograms or more of weapon grade HEU, has entered the dismantlement facility.

One form of attribute measurement involves the use of templates. Where there are a number of identical warheads, inspectors would take readings from a randomly selected warhead, to create a template against which the other warheads could be compared. It is not clear whether the characteristics of the DPRK’s nuclear arsenal are such that templating would be useful.

The idea of an attribute measurement system with information barriers was developed and demonstrated as part of the Trilateral Initiative undertaken by the United States, Russia and the IAEA in the period 1996 to 2002.8 The concept is proven, but further development may be required before it is ready for practical application. One area requiring further research is cyber-security aspects, ensuring that information barriers and authentication measures are not defeated. Attribute measurement was one of the techniques trialled in the United Kingdom-Norway Initiative on the Verification of Nuclear Warhead Dismantlement9, discussed below.

The dismantlement concept outlined above has been developed with a large weapon program in mind, and it may be possible to simplify it for the relatively small DPRK program. For instance, for a small number of warheads being dismantled in relatively short campaigns, attribute measurement might not be considered essential. If inspectors witness the transfer of say five warheads, each declared to contain at least “x” kilograms of HEU, into the dismantlement facility for a campaign expected to take say “z” weeks, then the DPRK would be expected to hand over to inspectors at least 5x kilograms of weapon grade HEU at the end of this period.

Cheating scenarios can be envisaged, for example:

(a) if the threshold value is set too low, the DPRK could submit four real warheads and a dummy (thus retaining one real warhead), knowing that the total recovered material will meet the expected threshold value:

– say the threshold value is 15 kg HEU/warhead, but each warhead actually contains 20 kg. The DPRK could submit four real warheads and one dummy. The inspectors would expect an output of 75 kg HEU (5 x 15), and would be presented with 80 kg, so all would appear to be in order, when actually the DPRK has withheld one warhead;

– this example suggests it is preferable to have attribute measurement of all warheads submitted for dismantlement;

(b) the DPRK could submit five dummy warheads each containing the threshold mass (say 15 kg HEU), while retaining the real warheads that contain a larger mass (say 20 kg HEU):

– on this scenario the DPRK appears to dismantle five warheads – in reality it has given the inspectors 75 kg of HEU, but still has the warheads.

Attribute measurement is more important if there are large numbers of warheads and there could be an extended period (maybe years) before the recovered fissile material could be correlated with the warheads submitted. With a small program the risk of cheating is reduced, but cannot be excluded. Ultimately confidence in disarmament depends on availability of complementary, mutually reinforcing information, such as nuclear archaeology (historical nuclear material balance substantiated by contemporary documentation and sampling at facilities and waste storage) and verification activities for providing assurance against undeclared missiles.10

5. The verifying entity

As discussed in section 3, most of the verification activities that would be involved in denuclearization in the DPRK are the same as or very similar to activities conducted by the IAEA in safeguards implementation. It follows that these activities could be undertaken by the IAEA, pursuant to a mandate given under a safeguards agreement concluded between the DPRK and the IAEA, or a mandate given by Security Council resolution. In due course a new safeguards agreement will be required between the DPRK and the IAEA. While some of these verification activities do not correspond exactly to a standard IAEA safeguards agreement, the IAEA Statute provides flexibility to conclude an agreement as requested by the parties.11

Other possibilities for the verifying entity, touched on below, include:

● nuclear-weapon states, or P5 (the Permanent Members of the Security Council) – either all the P5 or those most engaged with the DPRK (the United States, China and Russia);

● the parties to agreements with the DPRK pursuant to the denuclearization process – at this point it is not clear which states might be directly involved, the Six Parties again (the DPRK, United States, China, Russia, the ROK and Japan) or some other grouping. Possibly the parties might decide to establish a Joint Commission along the lines of the Iran JCPOA;

● bilateral arrangements between the DPRK and the United States;

● bilateral arrangements between the DPRK and the ROK, along the lines of ABACC (the Argentine-Brazilian Agency for Accounting and Control of Nuclear Materials);

● a regional safeguards inspectorate, along the lines of Euratom.

IAEA inspections can involve staff from non-nuclear-weapon states or nuclear-weapon states, commonly a mix of the two. Usually no distinction is made between the two groups of states. However, if the subject of an inspection is proliferation-sensitive, it is established practice to form a team of inspectors from nuclear-weapon states, comprising individuals having appropriate security clearances from the relevant national authorities.

For example, where the IAEA has been responsible for establishing that a nuclear weapon program had been terminated (South Africa) or investigating suspected nuclear weapon programs (Iran, Iraq, Libya, Syria and the DPRK), much of the verification work was undertaken by normal safeguards inspectors but, where necessary to protect classified information, tasks were assigned to inspectors who were appropriately cleared nationals from nuclear-weapon states, as just discussed. In some cases, teams were established that included non-staff specialists provided by nuclear-weapon states. Thus, the IAEA has developed substantial expertise in dealing with and appropriately protecting classified information.

As regards monitoring and verification of warhead dismantlement, the attribute measurement approach was developed in the context of bilateral arms control inspections between the United States and Russia – the objective was to enable an inspector from one state to confirm that an object presented by the other state is a warhead, without the inspector gaining classified information. Clearly this approach could also be valid for an inspector from a third state, or an international inspector, which is why the IAEA participated in the Trilateral Initiative. In other words, application of attribute measurement could be undertaken by inspectors from non-nuclear-weapon states.

The possibility of warhead dismantlement being verified by inspectors from non-nuclear-weapon states has been trialled in the United Kingdom-Norway Initiative, which has successfully conducted several practical exercises. The Initiative has involved three areas of work:

● managed access – how inspections can be carried out in practice;

● information barriers – procedural and technical measures to enable unclassified measurements to be made of a classified object;

● confidence in verification processes – including multinational participation in verification research.

The work of the United Kingdom-Norway Initiative has been an important input to the work of IPNDV. IPNDV has stated that “… actual dismantlement is the most important, complex, and technically challenging task of nuclear disarmament verification”, and has expressed the judgment that:

… while tough challenges remain, potentially applicable technologies, information barriers, and inspection procedures provide a path forward that should make possible multilaterally monitored nuclear warhead dismantlement while successfully managing safety, security, non-proliferation, and classification concerns in a future nuclear disarmament agreement.12 (underlining added)

In line with this judgment, there seems no reason why dismantlement of warheads in the DPRK could not be monitored by IAEA inspectors, which could include ROK nationals, and/or also by ROK government personnel. There is one caveat – because attribute measurement, and also the concept of monitored warhead dismantlement, are still in the development stage, there will likely be a need for specially qualified and cleared personnel from one or more nuclear-weapon states to oversee the operation to ensure there is no inadvertent transfer of classified information.

Non-IAEA monitoring and verification

It is possible there may be some resistance to early involvement by the IAEA in monitoring and verification in the DPRK. If this is delayed for any reason, monitoring and some other verification tasks could be undertaken by suitably qualified personnel from states involved in the denuclearization process (for example, the Six Parties, or a Joint Commission?) and from other states willing to support the process and acceptable to the parties.

There is some speculation that the DPRK may prefer bilateral verification arrangements, that is, inspections by United States personnel. This would present two difficulties. First is the question of credibility and integrity – will the international community have full confidence in inspections undertaken by the nationals of only one state, especially if there might be political pressures to reach favourable results? For this reason, multilateral inspections are the well-established international practice. Second, it should be recognized that the IAEA must be involved as soon as possible, having regard to the Agency’s nuclear verification mandate, its specialized expertise and equipment, and its international standing. The objective should be to develop DPRK-IAEA cooperation as soon as possible.

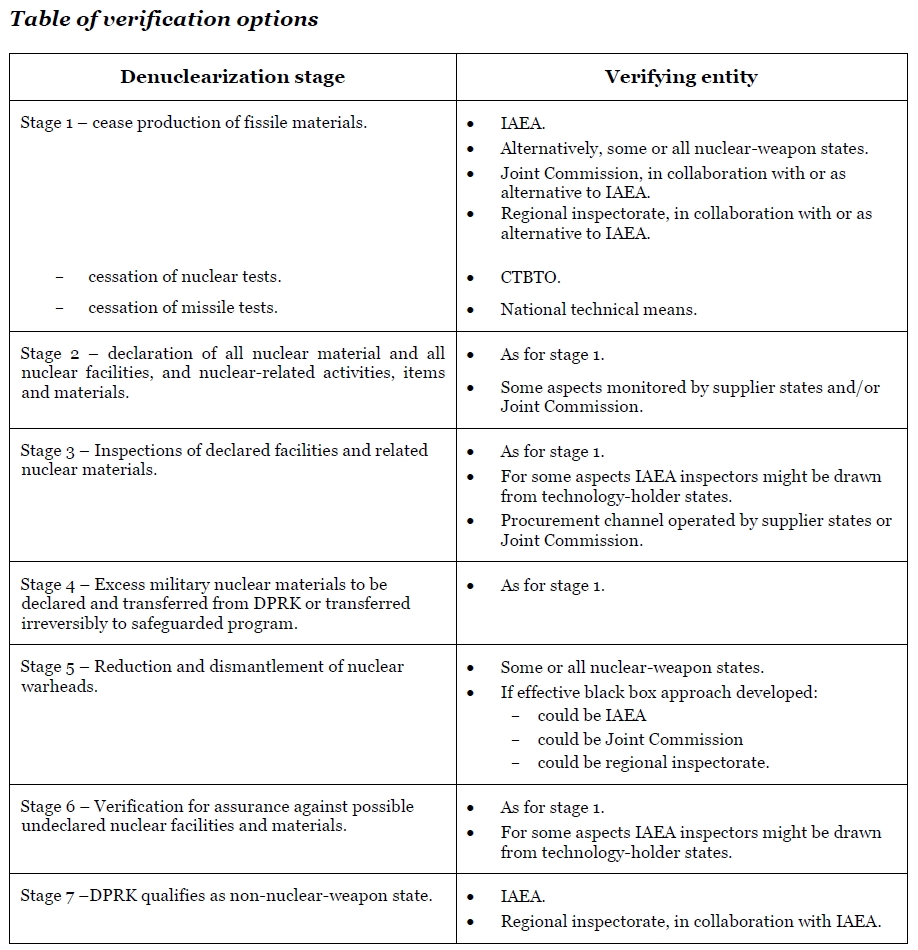

Summary of verification options

The following table summarizes the above discussion. In this table, Joint Commission is used to encompass either a formally constituted Joint Commission along the lines of the Iran JCPOA or a less formal grouping of parties to the denuclearization agreement(s) with the DPRK.

6. Possible ROK participation in denuclearization verification activities

If the ROK wished to participate in inspections in the DPRK the possibilities seem to be as follows:

(a) If initially, prior to agreement on IAEA involvement, monitoring and verification activities are carried out by Six Party or Joint Commission personnel, this is an opportunity for ROK participation. There are obvious advantages in having Korean inspectors in the team.

(b) Once IAEA activities start, ROK safeguards inspectors on the IAEA staff could join the team that the IAEA is likely to establish to carry out inspections in the DPRK. Here too there are obvious advantages in having Korean inspectors. However, it must be kept in mind that an inspected state can reject inspectors of specific nationalities, so it will be essential to ensure that the DPRK has no objection to ROK inspectors (this is also a possible issue under (a)).

(c) Another possibility is either bilateral safeguards arrangements between the ROK and the DPRK, or a wider regional safeguards inspectorate.

On a bilateral arrangement, the ROK and the DPRK might consider concluding arrangements similar to ABACC, under which safeguards inspections would be undertaken jointly by the IAEA and an ROK/DPRK bilateral inspectorate. It should be noted that although ABACC is generally thought of as a bilateral arrangement, actually it is more complex – it is a quadripartite arrangement, between Argentina, Brazil, ABACC and the IAEA.

It is for the ROK and the DPRK to consider whether a bilateral safeguards arrangement would be useful, for example, for transparency and confidence-building. It is important to note that the ABACC arrangements are reciprocal, so following this model would result in DPRK inspectors participating in inspections in the ROK as well as vice versa.

On a regional arrangement, the precedent is Euratom. Euratom was established a decade before the NPT, and it can be questioned whether a regional safeguards entity is warranted in today’s circumstances. Nonetheless, this is something states in the region, or states in the immediate neighbourhood, might consider – for example, whether an entity comprising ROK, DPRK, China, Japan, and maybe Russia and the United States (that is, the Six Parties) would serve a useful purpose. One way to look at this, quite different to the Euratom precedent, would be in support of the creation of a North Asia nuclear-weapon-free zone. If a regional safeguards entity were to proceed, the responsibilities of the IAEA would have to be accommodated, for example through a partnership approach as established between Euratom and the IAEA.

Treaty issues relating to ROK participation in denuclearization verification

NPT The key issue, in terms of the NPT, is whether the ROK’s participation in denuclearization verification activities could result in it acquiring information that could materially assist in the design or manufacture of a nuclear weapon. As a non-nuclear-weapon state Party to the NPT, the ROK has undertaken

“… not to receive the transfer from any transferor whatsoever of nuclear weapons … or … control over such weapons … directly, or indirectly; not to … acquire nuclear weapons …; and not to seek or receive any assistance in the manufacture of nuclear weapons …”13

Although the language of the NPT is not explicit, there is no doubt that acquisition by ROK nationals of data that could materially assist in the design or manufacture of a nuclear weapon would be considered a violation of the NPT.14 Also acquisition of data that could assist in the production of fissile material would raise difficult issues because of international concerns about any spread of proliferation-sensitive data.

The NPT places a corresponding obligation on nuclear-weapon states not in any way to assist any non-nuclear-weapon state to manufacture or otherwise acquire nuclear weapons.15 Thus the ROK must be scrupulously careful not to acquire, even inadvertently, any classified or proliferation-sensitive data, and nuclear-weapon states having control of such data through verification and monitoring in the DPRK must be scrupulously careful to prevent access to the data by a non-nuclear-weapon state.

Accordingly, the ROK must not be involved in any activity where it could acquire proliferation-sensitive data, and nuclear-weapon states in a position to do so must ensure that the ROK and other non-nuclear-weapon states do not acquire such data in the DPRK. As discussed in this paper, this does not mean a blanket exclusion from denuclearization verification in the DPRK. Many of the stages involved in denuclearization do not involve sensitive technology or information, or fissile material in sensitive forms or composition. There should be no objection to ROK personnel being involved in these stages.

Areas where ROK and other non-nuclear-weapon state personnel would have to be excluded include facilities where sensitive technology and information could be accessible (including weaponization activities, manufacturing of centrifuge components, and so on), and areas where nuclear weapon design and know how could be revealed. This is especially the case with warhead dismantlement (described as stage 5 in this paper), unless a black box approach with rigorous protective measures is established.

United States-ROK agreement concerning the peaceful uses of nuclear energy

The current agreement was concluded in 2015. The agreement reaffirms the Parties’

… strong partnership on strengthening the global nonproliferation regime … and close cooperation on advancing their shared objective to address the security and proliferation threat posed by North Korea’s nuclear program.

There are no provisions in the agreement that have a direct bearing on the issue of ROK participation in denuclearization verification in the DPRK. The Parties may agree on cooperation in research, development and demonstration, including safeguards and physical protection, and other areas as mutually agreed16 , but this language does not readily apply to verification implementation in the DPRK and there seems no reason why the Parties would seek to bring this under the terms of the agreement. Likewise, the Parties may agree to include under the High Level Bilateral Commission established pursuant to the agreement any topics related to peaceful nuclear cooperation mutually agreed to … by the Parties17, but there seems no reason why the Parties would seek to apply this to denuclearization verification.

The agreement could apply in the case of nuclear supply to the DPRK (for example, if nuclear supply is part of a denuclearization agreement), but this is beyond the scope of this paper.

Pros and cons for the ROK in participating in monitoring and verification in the DPRK

Pros:

● It would be a major plus for the ROK government to achieve DPRK acceptance of such a role; and also, recognition of the ROK’s co-equal status with the nuclear-weapon states.

● Most importantly, it could be a confidence-building measure between the DPRK and the ROK, smoothing the way for extending monitoring and verification arrangements to non-nuclear arms control measures in support of reducing tensions on the Korean peninsula.

● Taking a long-term perspective, in-depth involvement in dismantling the DPRK’s military program would reinforce the ROK’s understanding and capacity to deal with the DPRK’s nuclear weapon capabilities in a unified Korea.

● The ROK’s involvement might be implemented as part of a bilateral or a multilateral nuclear-weapon-free zone inspectorate that would also create a binding legal framework for the monitoring and verification activity between the disarmament process and the DPRK’s re-entry into the NPT, and give the three proximate nuclear-weapon states a formal role in DPRK denuclearization.

● ROK inspectors are the most likely of all to pick up cultural and other signals of deception and/or misunderstandings related to safety, security, and other limits imposed by the DPRK on monitoring and verification of its disarmament. Typically, the DPRK provides access and transparency in precise calibration to a mutually agreed rationale for such, and no more than minimally required. Being able to understand and negotiate that boundary is a critical conflict-avoidance issue in a monitoring and verification activity, to defuse such situations before they escalate into wars of words and then actions.

● The ROK may provide considerable logistical, technical, and financial support that could be hard to mobilize in the nuclear-weapon states.

Cons:

● The DPRK reaction may be strongly negative, adhering to the past view that this is a matter for the United States only (because the DPRK treats compliance with monitoring and verification as a way to get the United States’ attention, not because it wants monitoring and verification per se, let alone the involvement of the IAEA or other parties).

● It may complicate the negotiations over monitoring and verification in general, for example, by providing an argument for Japan that it too deserves to be confident that the DPRK has disarmed and to be treated co-equally.

● It could complicate the IAEA’s role if the DPRK objected to the ROK’s involvement.

● In the short to medium term some may suspect that the ROK wants to be involved as a way of gaining knowledge of how to produce nuclear weapons.

● It might be read as validating somehow that in the long run, a reunified Korea will combine ROK technological prowess with DPRK nuclear weapons knowledge.

7. Conclusions

There is a general view in the international community that nuclear disarmament verification should be undertaken as far as possible on a multilateral basis, in order to establish confidence in the integrity and credibility of the disarmament process. The main argument against a multilateral process is the possibility of classified and proliferation-sensitive information being compromised. However, a number of aspects of disarmament verification will not involve such information – for example, once fissile materials have lost classified form and composition, they are no different to comparable materials that are covered by IAEA safeguards. Further, IAEA safeguards demonstrate that a multilateral approach, incorporating special arrangements where necessary, can ensure the protection of sensitive information.

While it is absolutely crucial to both nuclear-weapon states and non-nuclear-weapon states to ensure effective protection of classified information, states should be prepared to consider on their merits internationally-developed approaches to meet this objective – a major focus of the IPNDV is to develop verification appropriate arrangements for non-nuclear-weapon state participation.

In the case of the DPRK denuclearization effort, the ROK has an obvious interest and every reason to be involved. This paper discusses a number of approaches to enable ROK participation consistent with the NPT’s non-proliferation principles. There are some challenges, but the parties involved in the denuclearization effort should be prepared to work collaboratively to address these.

References

A Verifiable Path to Nuclear Weapon Dismantlement, Dismantlement Walkthrough, IPNDV (accessed 14 November 2018), https://www.ipndv.org/learn/dismantlement-interactive/.

Denuclearizing North Korea: The Case for a Pragmatic Approach to Nuclear Safeguards and Verification, John Carlson, 38 North Special Report, 24 January 2019, https://www.38north.org/reports/2019/01/jcarlson012419/

Phase I Summary Report: Creating the Verification Building Blocks for Future Nuclear Disarmament, IPNDV November 2017, https://www.ipndv.org/reports-analysis/phase-1summary/.

IPNDV Working Group 2 – 2016-17 Output Report: Inspection Activities and Techniques, November 2017, https://www.ipndv.org/reports-analysis/deliverables-4-5-6-inspectionactivities-techniques/

Innovating Verification: New Tools and New Actors to Reduce Nuclear Risks, NTI, July 2014, https://www.nti.org/analysis/reports/innovating-verification-new-tools-new-actors-reducenuclear-risks/

Nuclear Disarmament: The Legacy of the Trilateral Initiative, Thomas E. Shea and Laura Rockwood, Deep Cuts Working Paper 4, March 2015, http://deepcuts.org/images/PDF/DeepCuts_WP4_Shea_Rockwood_UK.pdf.

Nuclear disarmament verification: the case for multilateralism, David Cliff, Hassan Elbahtimy, David Keir and Andreas Persbo, VERTIC Brief 19, April 2013, http://www.vertic.org/media/assets/Publications/VERTIC%20Brief%2019.pdf.

Trilateral Initiative: IAEA Authentication and National Certification of Verification Equipment for Facilities with Classified Forms of Fissile Material, Eckhard Haas, Alexander Sukhanov, John Murphy, IAEA Safeguards Symposium 2001, https://wwwpub.iaea.org/MTCD/publications/PDF/ss-2001/PDF%20files/Session%2017/Paper%201704.pdf.

UK-Norway Initiative on the Verification of Nuclear Warhead Dismantlement, https://ukni.info/; https://ukni.info/mdocs-posts/2012-npt-prep-com-presentation-theunited-kingdom-norway-initiative-on-the-verification-of-nuclear-warhead-dismantlement/.

1 John Carlson was director general of the Australian Safeguards and Nonproliferation Office. He was appointed as chairman of the IAEA’s Standing Advisory Group on Safeguards Implementation by former IAEA Director General Mohammed ElBaradei and served from 2001 to 2006. He also served as Alternate Governor for Australia on the IAEA Board of Governors. He is an Australian member of the Asia Pacific Leadership Network.

2 This report is published under a 4.0 International Creative Commons License the terms of which are found here. It is published by Nautilus Institute here; by the Asia-Pacific Leadership Network for Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament here; and by the Research Center for the Abolition of Nuclear Weapons, Nagasaki University, here.

3 Mention should also be made of Syria, where the IAEA’s investigation of a suspected nuclear weapon program has not progressed due to civil war. Of course, the other case of safeguards non-compliance was the DPRK itself, but the IAEA’s investigations were thwarted by the DPRK’s withdrawal from the NPT.

4 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action.

5 INFCIRC/66 safeguards agreements are described as “item-specific” agreements. They are used for non-NPT states, specifically India, Israel and Pakistan. Prior to joining the NPT in 1985, the DPRK had an INFCIRC/66 agreement covering the Soviet-supplied IRT reactor.

6 From IPNDV Working Group 2 Report of November 2017, page 89.

7 From IPNDV Working Group 2 Report of November 2017, page 36.

8 See Nuclear Disarmament: The Legacy of the Trilateral Initiative (References).

9 See References.

10 Missiles are considerably larger than warheads, hence are harder to conceal.

11 IAEA Statute Article III.A.5.

12 IPNDV, Phase I Summary Report, page 6.

13 NPT Article II.

14 Though probably not relevant in the context of DPRK denuclearization, it might be argued that acquisition of data in the public domain would not constitute a violation. However, there would be international concerns about a state’s motives in acquiring such data, and the NPT’s prohibition on seeking to manufacture nuclear weapons applies regardless of the status of the data involved.

15 NPT Article I.

16 See Article 3.

17 Article 18.